There’s something darkly funny about aviation safety guidelines: When an aircraft instrument fails or gives wrong readings, regulations require not just a warning sticker next to it labeled “INOP” (as in “inoperative”), but demand the instrument be physically deactivated or removed entirely.

Why? Because pilots, highly trained professionals who spend countless hours learning about instrument reliability and cross-verification, keep looking at them anyway.

I’ve experienced this myself flying a small aircraft recreationally. Despite the warning stickers next to the broken instrument, despite knowing better, your eyes are magically drawn to these dead instruments — as if staring at false readings long enough might somehow make them true.

Locking Up People in a Dark Room

This isn’t surprising given what we know about human decision-making under uncertainty. Suppose for a second that we were to conduct a psychological experiment in which we lock up 10 test subjects in a dark room without external stimuli for a few weeks. We would probably have trouble obtaining an ethics approval for this or finding voluntary participants in the first place, so let’s keep it hypothetical (assuming spherical test subjects in a vacuum, of course).

After 2 weeks have passed, we inform our participants that if they want to leave our dark room and get back to their families, they need to correctly guess the current time of the day, accurate to 2 hours. (Sounds like another likely reason for the ethics approval to fail.) This is a rather challenging task since humans begin losing track of time within a few hours of sensory deprivation — a point well illustrated by a self-experiment by Michael Stevens (Vsauce).

Of course, we are not cruel! Or at least not more cruel than can be expected from someone locking up people in a dark room. We therefore provide our test subjects with help: We offer them a very special clock that they are allowed to use for guidance if they wish. This clock is special indeed, in the sense that it is broken and the pointers have been stuck at a specific position for a very long but unknown amount of time. Great.

However, we are upfront about this to our subjects and tell them clearly that the time the clock is indicating has no connection to the current time. We even attach an INOP warning label to the clock.

Facing the choice of guessing the time completely on their own or requesting our clock as a helpful guide, what are our subjects going to do?

There’s a slight chance this clock is precisely correct at the time you are reading this article, misleading the unsuspecting reader to believe it is working.

There’s a slight chance this clock is precisely correct at the time you are reading this article, misleading the unsuspecting reader to believe it is working.

The Comfort of Wrong Numbers

From what we know about behavioral economics, most of our test subjects will request to use our clock. People usually prefer a bad measurement device to having none at all. They want the clock so they have at least some “information” to work with. They know it knows nothing, yet they still want to know what it says. That is how much we as humans hate uncertainty.

We also know from the anchoring effect that even just looking at this clock — that the subjects know to be dysfunctional — will introduce a bias into their guesses for the current time. Give all 10 participants a broken clock that says 2 pm and suddenly, their guesses will cluster around that specific value instead of being somewhat randomly distributed. But maybe they end up being lucky since even a broken clock is right twice a day, an effect very helpful to self-proclaimed experts.

“I Know That AI Knows Nothing.”

If you are using large language models like ChatGPT or Claude, you have probably noticed a small disclaimer below the text box saying “[Name of chatbot] can make mistakes. Please double-check responses.”

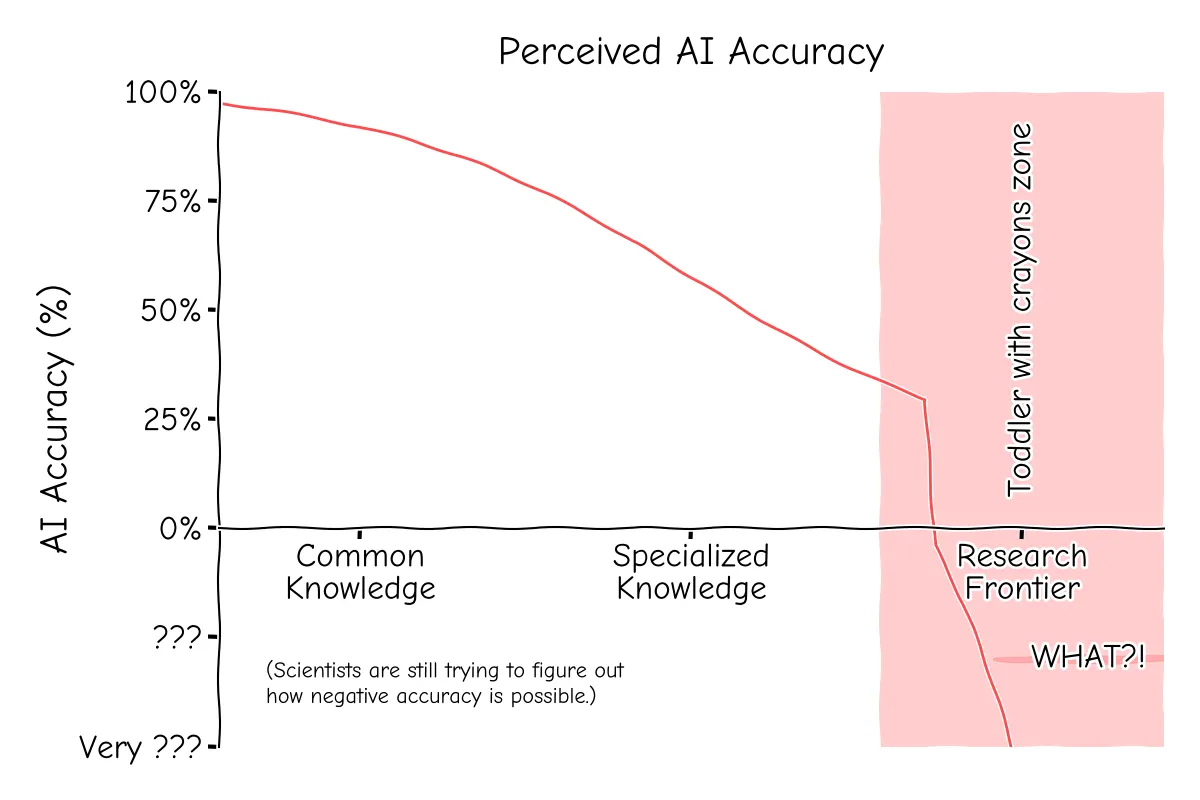

I work in physics research. I know that the answer to my research questions cannot possibly be out there in the web, otherwise there would be no point in conducting original research about it. But web data is precisely the information that was used to train the language models. As such, if the answer is not out there (or contained in some combination of the information), there is no way for the language model to provide me with it.

But in moments of intellectual laziness, say after the effect of my early-afternoon coffee has worn off at 5 PM on a Monday, that hasn’t stopped me from probing the chatbot for answers anyway. Of course, deep down I know it’s futile. Yet there I am, typing away, hoping that maybe, just maybe, the AI has somehow pieced together insights that I missed. It’s remarkable how quickly we can rationalize these moments of weakness: “I’m just using it as a sounding board,” or “Maybe it’ll give me a fresh perspective.” Sound familiar?

This problem only magnifies when a field becomes more specialized, as even less training data exists in the first place. We suddenly have wild inaccuracies popping up and the performance of our chatbot drops to the level of a toddler throwing crayons at the wall. In that case, I might as well ask the broken clock what the answer to my research question is. I then just interpret “2 PM” as “2 Pi” or something, which is more often than not a good guess in physics.

The more you know about a topic, the easier it is for you to see the AI’s limitations. Otherwise, it simply all sounds kind of reasonable.

The more you know about a topic, the easier it is for you to see the AI’s limitations. Otherwise, it simply all sounds kind of reasonable.

Beyond Warning Labels

So what do we do about this? When you feel the urge to use the “wrong clock” (or a language model for something it can’t possibly know about), remember the people trapped in that dark room, desperately staring at a broken clock.

The ideal technological solution would be for language models to simply refuse answering when their predicted accuracy falls below a certain threshold. But this would require actually being able to measure “accuracy” — and let’s be honest, making your AI look less capable isn’t great for venture capital pitch decks. So we remain stuck with answers that sound impressive but bear little connection to reality in truly interesting cases.

This highlights an inherent flaw in how LLMs are currently trained: they’re excellent at producing responses that look reasonable at first glance, but they lack any real mechanism for truthfulness. So the next time you’re tempted to ask an LLM something it couldn’t possibly know, remember: your brain will try to use that answer even if you tape a dozen “INOP” stickers to your screen. Some uncertainties can’t be resolved by staring at broken clocks — or chatting with confused AIs.

Though if you do catch yourself doing it anyway, take comfort in knowing that somewhere, in a dark room, a research participant is probably doing the exact same thing.